Birmingham trial aims to manage arthritis as a side effect of cancer treatment

A UK-first trial led by Birmingham researchers aims to improve treatment of arthritis in people who have developed the condition as a result of cancer immunotherapy.

The REmission induction of Arthritis caused by Cancer ImmunoTherapy (REACT) trial, led by the University of Birmingham and delivered through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), is one of the first global studies of its kind, testing whether powerful arthritis treatment is suitable for patients receiving ongoing cancer treatment.

REACT will recruit 70 patients across the country, and will investigate whether initial treatment with anti-TNF (anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor) therapy in cancer patients receiving a type of immunotherapy called an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), works to better control this type of arthritis – while not negatively impacting their cancer therapy.

Professor Benjamin Fisher, REACT’s Chief Investigator, Professor in Rheumatology at BHP founder member the University of Birmingham, and Lead for the Birmingham BRC’s Inflammatory Arthritis research theme, said: “Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionised cancer treatment, but they come with the risk of severe inflammatory side effects, including arthritis.

“The REACT trial aims to provide critical insights into the most effective initial treatments for patients suffering from this debilitating condition, potentially improving their quality of life significantly without affecting their cancer treatment.”

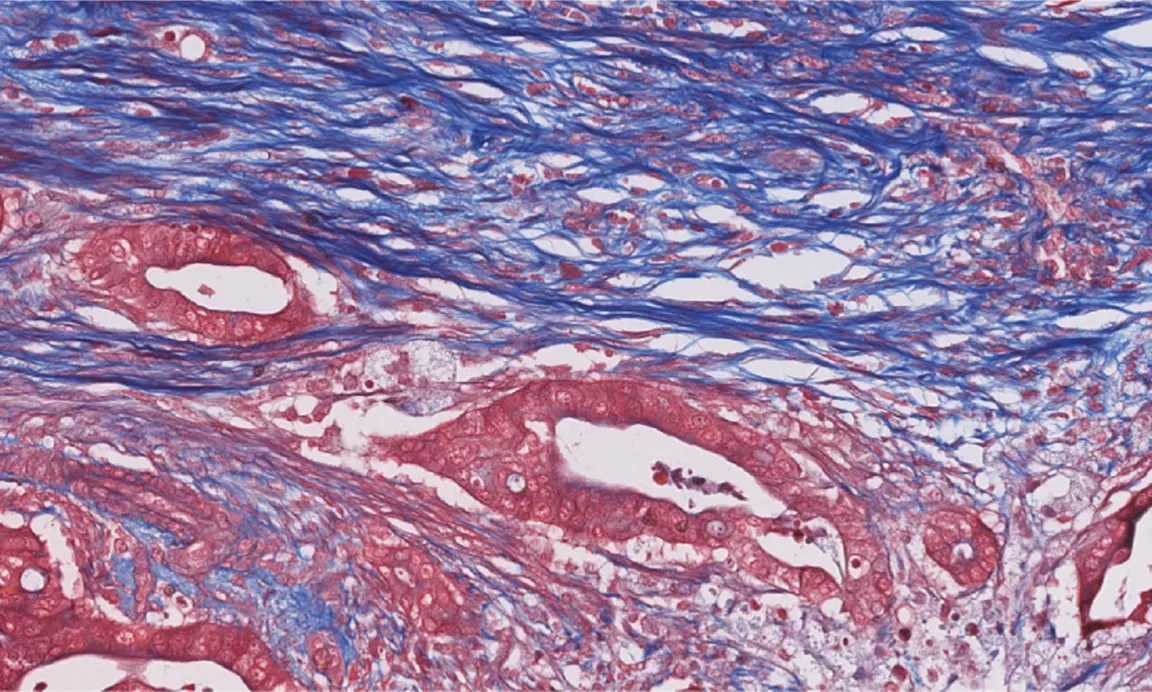

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are drugs that block the immune system’s inbuilt ‘off’ signals to help it fight cancer. While they are highly effective in treating cancer, they can also cause severe inflammatory side effects, including arthritis – which affects at least 5% of treated cancer patients and significantly impacts quality of life. It may persist even after ICI is stopped and may require treatment with drugs to suppress the immune system.

The typical treatment approach for arthritis that has resulted from ICI treatment is to start with steroid tablets, then gradually try other treatments if these fail. Anti-TNF is currently often the last treatment used.

TNF inhibitors have good evidence for other types of arthritis but there is no evidence for patients with ICI-induced arthritis to safely guide initial treatment strategy, so this trial will be the first to test the effects of immune suppressing drugs on cancer outcomes in response to ICI.

🗞️ BBC Midlands Today spoke to Becky Smith, who has received the new treatment as part of the clinical trial.

Becky (pictured above), 53 and from Solihull, was diagnosed with eye cancer in early 2020. Within weeks, she underwent surgery to remove her eye and adapted quickly to life with an artificial eye. For several years, she remained cancer-free – until the disease spread to her liver.

“I started immunotherapy last year, and while it offered hope, the side effects were brutal,” Rebecca explains. “I developed colitis, meningitis, and severe arthritis that attacked 90% of my joints. I couldn’t climb stairs, get dressed, or even get out of bed without help. It was devastating.”

These side effects forced Rebecca to take a year off work. “I love my job, but I simply couldn’t manage. Every cycle of treatment left me in hospital with side effects. It was a vicious circle.”

Standard steroid therapy offered little relief and clashed with her ongoing immunotherapy. That’s when her consultant suggested the REACT trial.

“I jumped at the chance. I thought, if it doesn’t work, at least I’ve tried – and maybe I’ll help others,” she says.

Rebecca was randomly assigned to receive adalimumab injections every two weeks. The impact was life-changing: “It’s been a godsend. My pain has eased, I can walk, I’ve returned to work, I can even wear heels again! My quality of life is back to what it was before.”

She still experiences mild aches before her next dose, but the improvement has been dramatic. “I’ve gone from being housebound to going on holiday and making memories with my family. Trials like this give people hope – and that’s priceless. Cancer and its side effects aren’t the end of the world. If you get the chance to join a trial, take it. It might change your life – it’s certainly changed mine.”

To compare the safety and effectiveness of these treatment strategies, the trial aims to recruit 70 ICI-induced arthritis patients across multiple centres in the UK. Participants will either receive current standard of care (initial steroid treatment in the form of prednisolone) or the anti-TNF drug adalimumab.

Treatments will be gradually reduced once the arthritis is controlled, or further treatment given if needed. The research team will compare the proportion of patients in each treatment group who have no arthritis and no steroid use 6 months after the start of treatment.

Researchers will also compare how fast the arthritis is controlled, and will continue to follow patients until one year to compare arthritis activity, quality of life, ability to function, total amount of immunosuppressive drugs received over time, number of ICI doses missed, new immune-related side effects, cancer outcomes and survival.

The clinical trial has received funding of more than £1 million from NIHR, supported by the NIHR UK Musculoskeletal Translational Research Collaboration and the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Birmingham Clinical Research Facility. The trial will run until August 2028 at the University’s Birmingham Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit (CRCTU), which is globally renowned for its academic excellence and enables innovative research with the potential to change lives, in both cancer and non-cancer fields like inflammatory diseases.