‘Vein-on-a-chip’ could help scientists study blood clots without animal models

Blood clot researchers could benefit from a new device that mimics a human vein, replacing the need for animals for some studies.

The vein-on-a-chip model has been developed by scientists at BHP founder-member the University of Birmingham, and can be used in experiments to understand mechanisms of blood clot formation in conditions such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

DVT is the development of blood clots in veins, usually in the legs. It is a serious condition because the clot can detach and travel to the lungs, where it may block blood vessels, causing breathing difficulties that prove be fatal. DVT is the third most common cardiovascular disease after myocardial infarction and stroke, with tens of thousands of people in the UK developing this condition every year. Mechanisms of deep vein thrombosis require further research to improve clinicians’ understanding and ability to treat or prevent the condition.

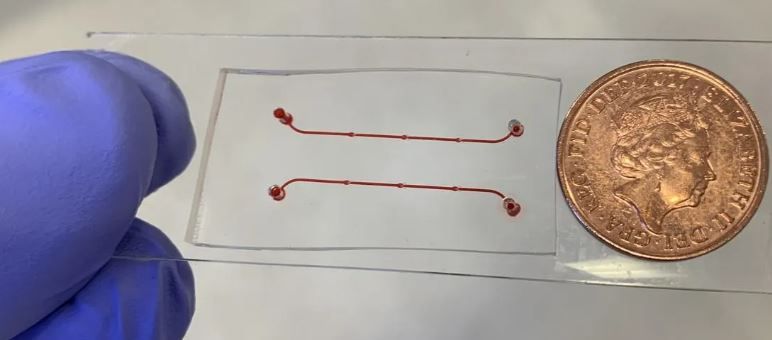

The new device, described in a recent paper published in Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, is a tiny channel, which includes structures called valves that ensure the correct direction of blood flow.

UoB researchers Dr Alexander Brill from the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, together with Drs Daniele Vigolo and Alessio Alexiadis from the School of Chemical Engineering, led the development of the new device.

Dr Brill said: “The device is more advanced than previous models because the valves can open and close, mimicking the mechanism seen in a real vein. It also contains a single layer of cells, called endothelial cells, covering the inside of the vessel. These two advances make this vein-on-a-chip a realistic alternative to using animal models in research that focuses on how blood clots form. It is biologically reflective of a real vein, and it also recapitulates blood flow in a life-like manner.

“Organ-on-a-chip devices, such as ours, are not only created to help researchers move away from the need for animal models, but they also advance our understanding of biology as they are more closely representative of how the human body works.

“The principles of the 3Rs – to replace, reduce and refine the use of animals in research – are embedded in national and international legislation and regulations on the use of animals in scientific procedures. But there is always more that can be done. Innovations such as the new device created for use in thrombosis research are a step in the right direction.”

This research was funded by the NC3R, British Heart Foundation and Wellcome.