Pancreatic cancer cell ‘atlas’ uncovers why many promising treatments fail

The most detailed atlas of tumour cells from the deadliest form of pancreatic cancer has been developed by an international team of researchers, highlighting how tumour cells change their behaviour depending on their surroundings – and how this leads many promising treatments to fail in standard lab tests.

The research was a collaborative effort led by the BHP founders-members the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, working with pharmaceutical company Bristol Myers Squibb. Published in Cell Reports, their findings describe the most detailed spatial map to date of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

In the study, tumour samples from 39 untreated pancreatic cancer patients were analysed using cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics technologies, allowing researchers to see which genes are active in cells and exactly where those cells are located in the tumour. This approach generated a massive dataset – comprising hundreds of thousands of spatial measurements and more than half a million individual cells – creating a comprehensive ‘atlas’ of pancreatic cancer tissue.

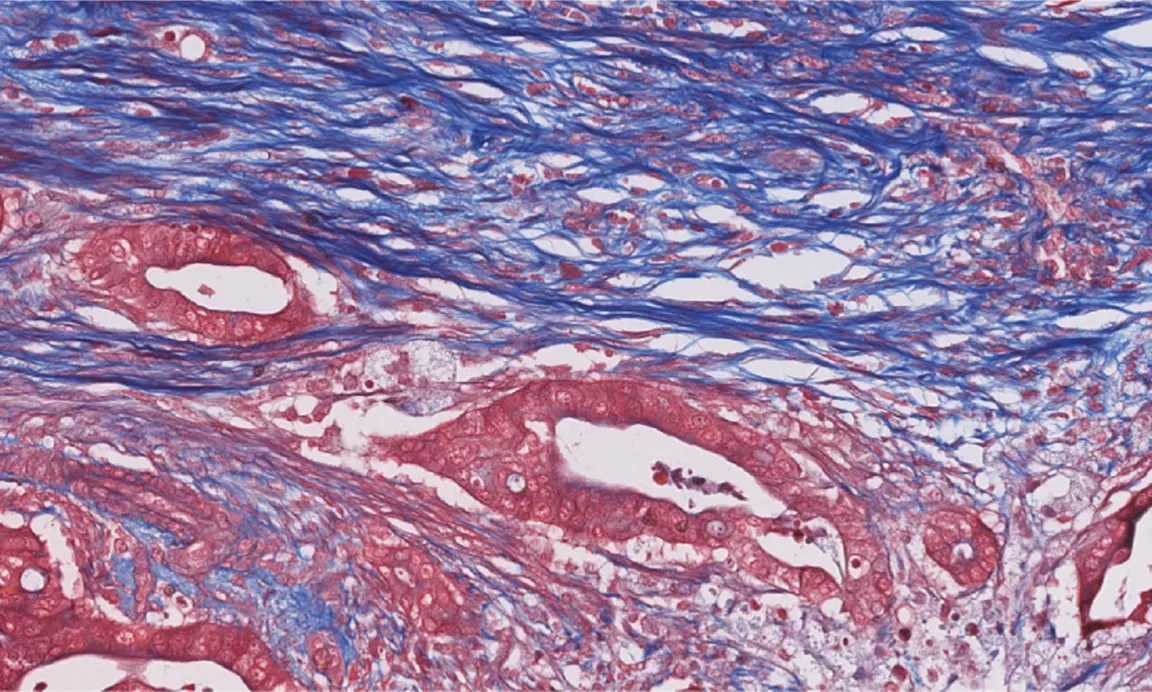

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the hardest cancers to treat, with few effective therapies and a five-year survival rate in the single digits. A major reason is the disease’s complexity: cancer cells are embedded in a dense, hostile tissue environment filled with scar-like material, low oxygen, and supportive cells that help tumours survive.

Dr Shivan Sivakumar, co-senior author from the University of Birmingham and consultant medical oncologist at University Hospitals Birmingham said: “This spatial atlas is expected to serve as a foundational resource for the research community, and may accelerate the development of treatments for a disease that has long resisted progress.

“By integrating spatial biology with functional genetic screening, we have created a roadmap for discovering therapies that target pancreatic cancer more effectively – especially combination treatments designed to disrupt both cancer cells and the environments that protect them.

“The findings suggest that environmental factors play a much greater role in tumour cell development in the pancreas, and identifies new intermediate tumour subtypes and highly proliferative cancer cells which together provide a more vivid picture of this deadly cancer.”

Dr. Konstantinos Mavrakis, Executive Director and Head of Discovery Biosciences Oncology at Bristol Myers Squibb and co-senior author of the publication emphasised the importance of scientific collaborations: “This study underscores how important it is to use real-world patient data to better understand the underlying causal human biology of a specific cancer type such as pancreatic cancer.”

Key findings:

- Cancer cell identity depends on location. The study confirmed known pancreatic cancer subtypes, commonly called classical and basal-like, but showed that these identities are strongly shaped by the tumour’s local environment. In particular, aggressive basal-like cancer cells were consistently found in regions with low oxygen and dense fibrotic tissue.

- A hidden cancer state comes into focus. Researchers discovered that an ‘intermediate’ tumour subtype is not just a mix of known states, but a distinct cancer cell identity. This finding clarifies long-standing confusion in pancreatic cancer classification.

- Tumours contain a small but powerful growth engine. A previously underappreciated group of highly proliferative cancer cells was identified, marked by intense cell-division activity. Although relatively rare, these cells may disproportionately drive tumour growth.

- Context hides critical vulnerabilities. The team used CRISPR gene-editing screens in cancer cells grown under realistic conditions such as low oxygen or inside living tumours. This revealed genetic weaknesses that are invisible in standard laboratory cultures, and may explain why many drug targets that look promising in the lab fail in patients.

- Common lab models miss key disease features. Widely used mouse and cell-line models captured some aspects of human pancreatic cancer but often failed to reproduce the most aggressive tumour states and their surrounding environments. This highlights the need for better preclinical testing strategies.